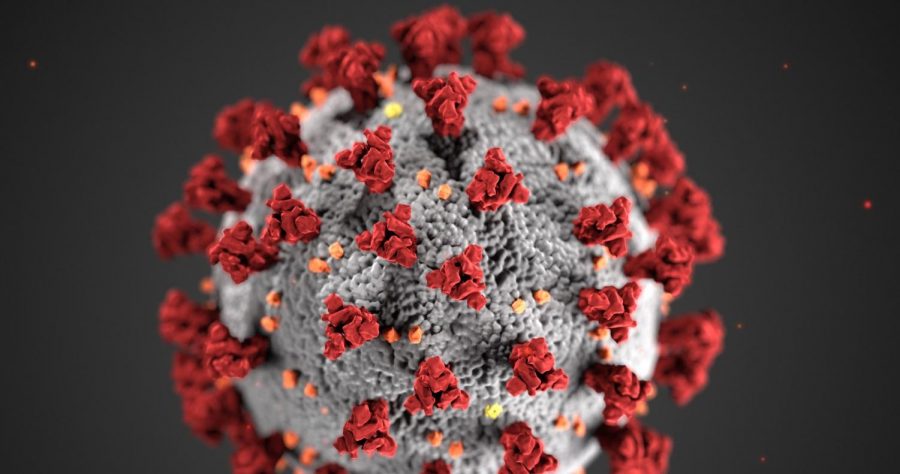

Research shows the lineage of COVID-19 and its mutations and how this helps with making vaccines.

A new variation of COVID-19 has U.K. researchers and others concerned

April 9, 2020

New research suggests the strain of COVID-19 was present in the United States as early as mid-February in New York, weeks before the first confirmed case, and the virus mainly came from Europe, not Asia, according to a New York Times article.

Harm Van Bakel, a geneticist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who co-wrote a study awaiting peer review, concluded with a separate team at N.Y.U. Grossman School of Medicine, that despite them studying a different group of cases, both teams analyzed genomes from coronavirus taken from New York starting mid-March. The research revealed a previously hidden spread of the virus that might have been detected if aggressive testing programs had been put in place.

“The majority is clearly European,” Van Bakel said.

Regulations such as foreign nationals barred from entering the country if they had traveled to China during the prior two weeks were in place on Jan. 31 but it would not be until March 11 when President Trump blocked travelers from most European countries from entering the U.S. after Italy began locking down towns and cities.

By this time, New Yorkers had already been traveling home with the virus, according to the New York Times article.

“People were just oblivious,” Adriana Heguy, member of the N.Y.U team said.

Dr. Heguy and Dr. Van Bakel have studied the genetic material of viruses taken from thousands of patients.

When the virus invades a cell, it takes over its molecular machinery, causing it to make new viruses, according to the article, as a result, the new virus manages to escape its host and infect other people and therefore its descendants will inherit that mutation.

Sophisticated computer programs can figure out how the mutations arose as viruses descended from a common ancestor and if they get enough data they can make rough estimates about how long ago those ancestors lived, since mutations arise at a roughly regular pace.

The virus’s genome, SARS-CoV-2 makes it clear that it arose in bats according to Maciej Boni and his colleagues of Penn State University. While there are many kinds of coronaviruses that infect both humans and animals, Dr. Boni and his colleagues found that the genome of the new virus contains a number of mutations in common with strains of coronaviruses that infect bats, according to the NYT article.

Researchers found that the Chinese horseshoe bat is the most closely related coronavirus but the new virus COVID-19 has gained some unique mutations since splitting off from the bat virus decades ago.

Dr. Boni stated that in the past 10 or 20 years it is possible a hybrid virus arose in some horseshoe bat that was well-suited to infect humans, too. Later, that virus somehow managed to cross the species barrier, according to the NYT article.

“Once in a while, one of these viruses wins the lottery,” he said.

When a team of Chinese and Australian researchers published the first genome of the new virus this opened up for the world of researchers to compare and contrast the cases in their respective countries. They sequenced more than 3,000 genomes and found some are identical to each other while others carry distinctive mutations.

When new genomes are discovered, researchers upload them to a an online database called GISAID originally known as Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data, used to share information on the influenza pandemic with researchers around the globe.

A team of virus evolution experts are continually updating the virus family tree in a project called Nextstrain where the deepest branches of the tree all belong to lineages from China.

The team has also used the mutation rate to determine the virus probably first moved into humans from an animal host in late 2019 and according to the NYT article China announced on Dec. 31, that doctors in Wuhan were treating dozens of cases of a mysterious new respiratory illness.

As it became clear the struggles China was up against, a few countries started aggressive testing programs where they were able to track the arrival of the virus on their territory and track its spread through their populations, according to NYT article.

But during this time the United States was only testing people who had come from China and displayed symptoms of COVID-19.

“It was a disaster that we didn’t do testing,” Dr. Heguy said.

According to the New York Times article the Washington viruses also shared other mutations in common with ones isolated in Wuhan, suggesting that a traveler had brought the coronavirus from China.

Dr. Trevor Bedford, an associate professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the University of Washington showed with Nextstrain that a virus identified in a patient in late February had mutation shared by one identified in Washington on Jan 20.

The same viruses also shared other mutations in common with ones isolated in Wuhan, suggesting that a traveler had brought the coronavirus from China according to the article.

The best results come with more information in sequencing genomes and this allows for a better view of how the outbreak started.

Mutations do not automatically turn viruses into new, fearsome strains according to Sidney Bell, a computational biologist working with the Nextstrain team and says “To me, mutations are inevitable and kind of boring, but in the movies, you get the X-Men.”

The good news for scientists working on a vaccine is that COVID-19 has a relatively slow mutation rate compared to some viruses, such as influenza and by tracking its history and knowing that mutations don’t necessarily change how the virus works, one vaccine could be all that’s necessary.